J. S. Beach

9-copy edition series + 2Aps

The experience of a world that is too full, of interior spaces too much furnished by the futile and banal, is typical of men and women of the Twentieth and Twenty-first centuries. It was Walter Benjamin who spoke of a “furnished man” to explain the colonization of inner space made by objects, images and sounds that literally left no room for reflection, for being alone, for thinking and listening. The interior space is so colonized by unrelated “things” that it is difficult for us to find a moment for that penetrating and profound solitude from which artistic inspiration or philosophical intuition arises; even when we are alone the world penetrates us, not with the legitimate need for sociality and socialization (because of we are never completely alone because the whole world is reflected within us) but with a cumbersome and not required presence. We are inhabited by the world and this makes it difficult for us to live it in a proper and complete sense.

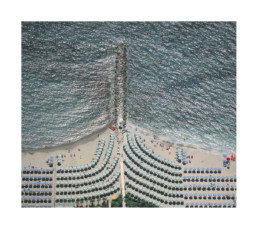

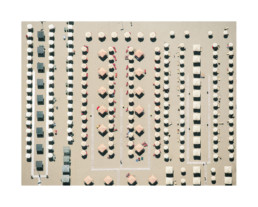

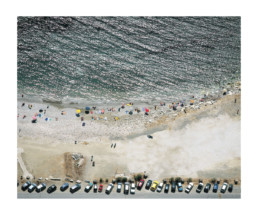

So, we need a pedagogy of empty spaces as a preliminary operation of an education of the soul; it is necessary that the people are trained to create within themselves what we call white holes, i.e. fragments of interiority that we save from the siege, rectangles of meaning and of self that we subtract from the dictatorship of a world that furnishes us inside. If it is necessary to teach to create your own white holes, it is however true that there is no white holes in our inwardness if there are no external spaces and times of disengagement. It is by researching or creating the white holes in one’s day and in one’s life and one’s work environment, that one can create the conditions for an inner spiritual emptiness. The series of photographs presented by Stefano Baroni in the exhibition Migrazioni, can be identified as a sort of aesthetic interpretation of the world where we live in, that tries to provide alternatives to the classic stereotypical vision of reality and to the possibility of moving a few millimeters laterally, the normal sense of understanding. The attempt is not to pursue an aesthetic ideal, but, on the contrary, to try to demolish the meaning of things through structures derived from the things themselves.

Abstraction, a way to introduce this body of work, a new exploration guided by a rigorous attention to the essential, a formal purity capable of momentarily suspending the uninterrupted flux of images and the infinite possibilities available with post-production. A space presented in silence where the lines give form and structure to the planes of color and the irregular flows. An aesthetic of subtraction and reduction of a world overcrowded with images and words which direct our perception towards these formats which play out through linear composition and chromatic intensity, through the space-time relationship to help us discover the immediate look of the pure sensation, that is the effect of a simple visual impression. Simultaneously, these planes, animated by the dynamics of color, serve as a metaphor for real space, while also dissolving into a purely emotional experience and sensation. The viewer’s experience of these works is like that of flickering emotions in the intensity of color and its variation, in their juxtapositions or in the interruptions created by a white space. This can be used as a starting point for the interpretation of this body of work, contextualized within a mechanism of contemporary art where artists move freely and fluctuate in constant experimentation, albeit pursued with logic and articulated according to specific rules. The most common mistake made by viewers today is to naively think that the work before them has always been and will always be as it is seen at that particular moment, not allowing for the fact that an artist’s exploration can and does change with time, or that he may consider new experiments with regard to form, concept, or technique.

Roland Barthes wrote that the name of the noema of photography coincides with the verbal form “has been”, i.e. with something that, at the moment of shooting, was there, in that place, and then immediately after separated from this link and became something different. Each photo is therefore the testimony of something necessarily real, which is placed before the objective. According to Barthes, therefore, the reference is the founding order of photography. These words on photography serve to give an objective reading of the work proposed by Stefano Baroni who, always starting from a real datum, then arrives to something different, but always starting from the real matrix of the surrounding reality. In the specific case of the exhibition Migrazioni, the artist starts from a photograph taken from a crowd of people who, thanks to a post-production work, has come to generate another image that takes the form of a colorful spiral almost as if it was the movement of a vortex formed by a myriad of pigments. Colors that we find with more regular and linear trends horizontally and vertically, just like the large digital prints of 2011 by Gerhard Richter entitled Strip, composed of a rigorous parallel line system. However, the starting point for Strip is a painting (as for Baroni is the photograph of a thing or a real fact), created by the artist in 1990: Abstract painting (724-4). With the help of a software, he divided vertically this work, first in two parts, then in four, eight and so on, and finally this process led to the creation of strips of the same height of the original painting from which the project started. The state of painting (and photography in the case of Baroni) in these new works appears as exceptionally fragile, yet it is powerfully formulated in its assimilation to its technological challenges, as if painting is once again in a sort of decline under the impact of technological innovations.